Here in the BYU SE lab, we’ve been analyzing the way that failures cascade between system components. From 40 publicly published incident reports, we have identified over 100 failure pairs, which are simply two failures in different components, where the first failure is described as being the cause of the second failure. In a series of posts we’ll be sharing some of our early findings. For more details about our data set and some of our preliminary findings see Barbara Chamberlin’s MS thesis.

Temporal patterns

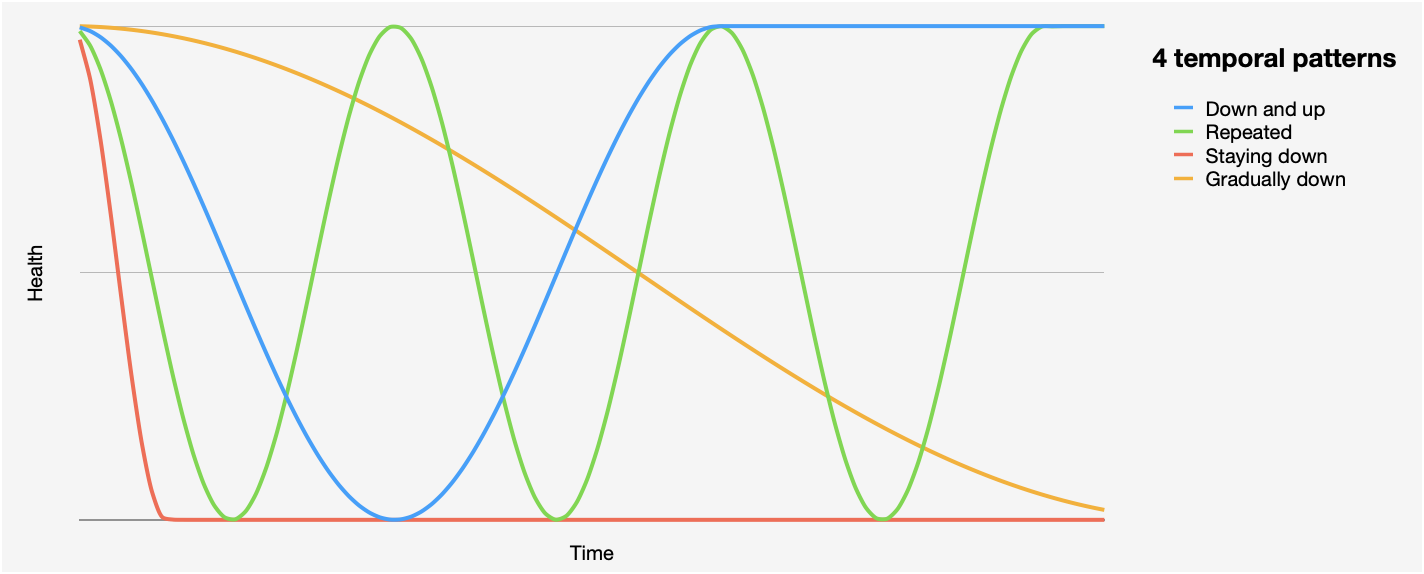

While studying cascading failures, one interesting dimension we’ve explored briefly is the temporal relationship between the two failures. Put another way, this is about how the first failure unfolds over time and then (as a consequence) how the second (cascading) failure unfolds along with it.

Sometimes this is pretty straightforward and as (possibly) expected: the first failure happens relatively quickly (a component is healthy and then it isn’t) and then the second failure happens more or less immediately after the first. But in other cases, the temporal relationship was a bit more notable and so we looked at these “other cases” a little more closely, and came up with four simple patterns.

-

Down and up. The first component fails in some way and then recovers, and interestingly the failure in the second component happens as the first component recovers rather than when it first fails. One of the most common reasons for this is that when the component is down, a large backlog of work can be accumulated (maybe unsent messages being stored in a queue) and while that component is recovering, the backlog is processed and cause some overload. We also saw this happen when the recovery path contains a defect, when failover (like, a database failing over to a new primary) is mishandled, and when a restart doesn’t go as planned.

-

Repeatedly down and up. When a component repeatedly fails and quickly recovers, that instability can cause cascading failures (failures that would not happen if it just went down and stayed down, it seems). In one example, a bunch of nodes mirrored data from an authoritative store AND whenever there was an interruption the nodes requested a complete copy of the mirrored data. Well during periods of instability this led to a storm of resynchronization requests (and more instability, actually). In another example repeated reconnections increased the effect of a resource leak causing a crash.

-

Staying down. Some cascading failures happen because of how long an initial failure lasts, and might have been avoided if there was a quicker recovery. In other words, the initial failure could be tolerated but only for so long. A good example is when messages are being deferred (while some component is unavailable, with the plan of sending those messages when it is available). These can eventually cause out-of-memory crashes. (And like we mentioned above, the more messages that are deferred, the more work there will be to process during recovery.)

-

Gradually down. Some failures happen gradually. That is the extent to which it is degraded increases over time (think, gradually increasing failure rates, say). Now sometimes dependencies (or other affected components) may also degrade gradually right along with the initial failure. But in other more interesting cases, the dependency will only fail when a certain degraded threshold is reached, suggesting an interesting kind of step function relationship.

The key implication here is that when we are trying to avoid cascading failures (presumably, using techniques like timeouts and retries, queues, etc) we need to think about how initial failures may play out over time.